Our population handicap

The Philippine national hunger problem would not be as hard to manage if there were not as many as 28 million families—the family, not the individual, is the Social Weather Stations hunger unit—to regularly provide with food. Nor would the traffic problem be as difficult if there were not as many as 10 million adults in the National Capital Region. Only 50 years ago, there were less than half as many to provide for.

Everyone knows that population grows at a compound rate. As people reproduce, there are more of them who can reproduce. The Law of 69 is inexorable: if something grows at X percent per year, then it will double in size in 69 divided by X years. In the 1960s, our population grew by 3 percent per year; therefore, it was bound to double in 69/3 = 23 years, or only a single generation.

That the Filipino people went from 42 million in 1975, to 78 million in 2000, to 119 million in 2024, is no surprise. Even though the annual population growth rate has now been halved to 1.5 percent, at this rate it will be only 46 years until the population doubles again. How does the Philippines cope with a 200+ million population in 2070? I won’t be around to see it, but half of those alive today (with the median age at 25), including my children, probably will.

Research that looked toward the year 2000. By the late 1970s, researchers the world over got very concerned about the new millennium. In 1976-1977, the Development Academy of the Philippines (DAP) formed a consortium with two units of the University of the Philippines—the Population Institute (UPPI) and the School of Economics (UPSE)—to work on the research project “Population, Resources, Environment and the Philippine Future” (PREPF). The main sponsor of the project was the Population Center Foundation. I chaired the consortium’s steering committee, wearing the DAP and the UPSE hats, while National Scientist Mercedes Concepcion, the demographer, wore the UPPI hat. The PREPF project’s many technical papers were condensed into in a 222-page book, “Probing Our Futures: The Philippines 2000 AD,” published by DAP, UPPI, and UPSE in 1980.The PREPF study did very many demographic projections, using alternative assumptions for low, medium, and high rates of family formation, birth rates, death rates, etc. It worked out scenarios for the people’s health, education, and distribution of income. It asked how long our natural resources would last unless new discoveries happen (sorry, I don’t recall what the answers were).

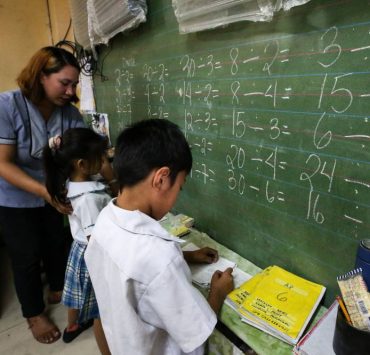

We saw that the poor had larger families than the rich. It made sense, given the weak social security system, for couples to seek enough children to be their support in their elder years. There was not much family planning, due to lack of contraceptive methods and facilities, especially for the poor. Actual pregnancies outran wanted pregnancies; the demand for family planning was unfilled. Education of all persons in general, but especially of women, was seen to promote nonexpansion of family size. Restraint in fertility would generally improve family well-being.

I don’t recall that we researchers worried much about the Philippines’ falling into a Malthusian trap, with an economically unsupportable population getting trimmed down by plague, pestilence, and war. In effect, we were trusting in the saying that “with every mouth, God creates a pair of hands.”

The very fact of such research being done, in many countries, showed worldwide acceptance of the urgency to restrain population growth. Unfortunately, this urgency was not taken as seriously in the Philippines as elsewhere. (Were many politicians loath to offend the Catholic Church? I think they needn’t have worried, since our surveys show hardly any influence, positive or negative, of the Church on the people’s votes.)

The Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam used to be roughly equal in population. But the Philippines has overtaken the other two countries and is now second to Indonesia (278 million), within Asean. The Vietnamese are 99 million. The Thais are now only 72 million, thanks to the efforts of family planning activist Mechai Viravaidya, affectionately dubbed “Mr. Condom,” who thereby won the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Public Service in 1994.

In terms of the annual population growth rate, the Philippines’ 1.54 percent is the highest in Asean, followed by Timor Leste 1.44, Laos 1.39, Malaysia 1.09, Cambodia 1.06, Brunei 0.78, Indonesia 0.74, Myanmar 0.74, Vietnam 0.68, Singapore 0.65, and Thailand, 0.15 (source: worldometers.info, 7/16/23). Note that Thailand has virtually reached zero population growth (ZPG). I think the Philippines should aim likewise for ZPG, starting perhaps by promoting four as the ideal family size.

China’s draconian one-child policy of 1979-2015 succeeded in reaching ZPG. China’s population is already falling; its latest annual growth rate is -0.02 percent. China has 1.425 billion people, versus India’s 1.428 billion; the gap is widening, with India’s latest annual population growth at 0.81 percent. Yet, not content with ZPG, China is scouring the world for more minerals. It has long been eyeing the Philippine seas, on both our western and our eastern sides.

Contact: mahar.mangahas@sws.org.ph.

Dr Mahar Mangahas is a multi-awarded scholar for his pioneering work in public opinion research in the Philippines and in South East Asia. He founded the now familiar entity, “Social Weather Stations” (SWS) which has been doing public opinion research since 1985 and which has become increasingly influential, nay indispensable, in the conduct of Philippine political life and policy. SWS has been serving the country and policymakers as an independent and timely source of pertinent and credible data on Philippine economic, social and political landscape.