Poverty as defined by the poor

The current controversy over the official poverty line is due to social critics’ intense disagreement of where to draw the line. The government has an official opinion, presumably based on official criteria. All are entitled to their opinions, but it seems not many are publicly supporting the official side.

How can disagreements be resolved? Is there is a social consensus on where to draw the line? How about this multiple-choice probe: a. “The official poverty line is probably too high,” b. “The official poverty line is probably too low,” c. “The official poverty line is probably correct,” and d. “I don’t know enough about the official poverty line to be able to choose.” [Avoid sequence bias by writing the options on cards, shuffle the cards, and lay them out to choose from.]

The above probe is not for Social Weather Stations to do, because we already have our own way of monitoring poverty, which is more rapid and more frequent, than the official way. As I wrote in “Poor, Borderline, Not Poor” (inquirer.net, 7/20/24), Filipino families are able to identify with one of these three groups, when shown the words “Poor” and “Not Poor” separated by a line. Last June, the proportions of the three groups were 58, 12, and 30 percent respectively (see “Second Quarter 2024 Social Weather Survey: 58% of Filipino families feel Poor, up from 46% in March 2024,” www.sws.org.ph, 7/18/2024).

SWS identifies the Poor first; then it asks their need for home expenses. SWS does not define the poor by means of a line. Rather, first it lets the Poor identify themselves, and then it asks those feeling Poor how much they need for monthly family home expenses, in order not to feel that way; this gives the Poverty Threshold for the quarter. This threshold is for a family, not for an individual. It is for home expenses, i.e., it excludes work expenses like commuting. It is per month, not per day. These are common units that respondents can understand.

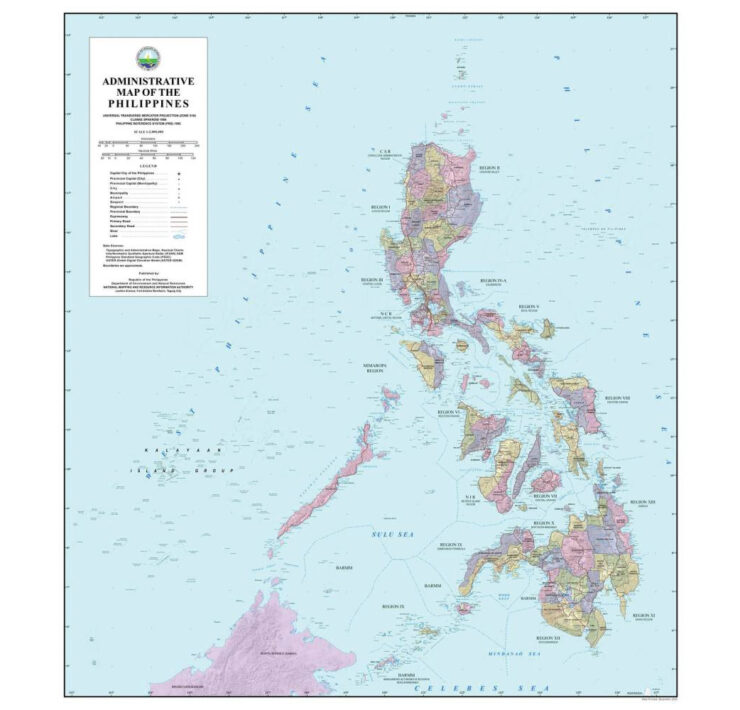

Poverty thresholds have a wide range, due to variance in cost of living across areas. They are typically highest in the National Capital Region. NCR’s 39 percent self-rated poor had a median threshold of 20,000 pesos per month last June, i.e., 19.5 percent of NCR families had less for their home expenses than that.

Balance Luzon’s 52 percent poor had a median threshold of 15,000 pesos, Visayas’ 67 percent poor had a median threshold of 10,000 pesos, and Mindanao’s 71 percent poor had a median threshold of 12,000 pesos. In each area, half of the poor were below the median.

The people’s poverty thresholds in the SWS reports are whatever the survey respondents declare, at the time surveyed. Respondents typically state their thresholds in large round numbers, like thousands, not mere hundreds, of pesos. Over time, these thresholds tend to rise, in line with inflation in the cost of living. But now and then they fall, indicating times when the poor are tightening their belts, which I think is realistic , too.

SWS identifies the Food-Poor first; then it asks their food-budget need. Similarly, SWS does not define Food Poverty by means of a predetermined line. Rather, it lets the Food-Poor identify themselves by the same Mahirap/Hindi Mahirap show-card used for Self-Rated Poverty, applied to the quality—not quantity, since SWS has other survey questions about hunger—of their current food. Afterward, it asks those feeling Food-Poor how much they need for monthly food expenses in order not to feel that way; this gives the Food Poverty Threshold.

A food poverty threshold is for a whole family, not one person. It is per month, not per day. Most definitely, it is not per meal. SWS does not ask if a family does all its own cooking or if it buys cooked food.

Like general poverty, Self-Rated Food Poverty rose in the second quarter of 2024, to 46 percent in June from 33 percent in March. The latest percentages of Food-Poor families are 31 in NCR, 42 in Balance Luzon, 50 in Visayas, and 61 in Mindanao.

The latest median monthly Food Poverty Thresholds are P10,000 in NCR, P8,000 in Balance Luzon, P7,000 in Visayas, and also P7,000 in Mindanao. These are the monthly food budgets that half of each area’s food-poor families say they need to escape food poverty. I think they are realistic.

—————-

mahar.mangahas@sws.org.ph

Dr Mahar Mangahas is a multi-awarded scholar for his pioneering work in public opinion research in the Philippines and in South East Asia. He founded the now familiar entity, “Social Weather Stations” (SWS) which has been doing public opinion research since 1985 and which has become increasingly influential, nay indispensable, in the conduct of Philippine political life and policy. SWS has been serving the country and policymakers as an independent and timely source of pertinent and credible data on Philippine economic, social and political landscape.