‘Sleepwalkers’: Is Sara presidency inevitable?

LONDON—One of the greatest handicaps of our democratic life is the poverty of our political discourse. To quote the great commercial banker Stephen CuUnjieng, we have an oversupply of ”lazy thinking.” We see this phenomenon even at the supposedly highest echelons of technocracy.

From Toronto to Tokyo, from Paris to Perth, and from Washington to Wollongong, there is spirited debate over the future of economic policy, with a particular focus on ”industrial strategy.” This is even true in the cradle of ”neoliberalism,” namely, the United Kingdom, where new national security considerations are reviving age-old anxieties over the country’s long-term deindustrialization under the shadow of Thatcherite shock therapy.

We see exactly the same trend across the developing world, including in neighboring Malaysia, which has its own Japan-inspired Ministry of Investment, Trade, and Industry. Even the historically extractive Indonesia is stubbornly pursuing its own version of ”industrial policy” by, inter alia, localizing export minerals processing and ramping up local-content car manufacturing. Even more impressive is Vietnam, which has, in less than a decade, built a globally recognizable national car brand, VinFast—the Vietnamese Communist Party’s de facto ”national champion.” Contrast this with the Philippines, where we are still stuck with macroprudential policy and the latest iteration of “daang matuwid” with barely any rigorous discussion of a new national economic strategy beyond remittances, business process outsourcing, and low-end services.

A good chunk of our publicly spirited economists seem more busy with politically resonant anticorruption activism than with cutting-edge economic research. Instead of engaging post-neoliberal world-renowned thought leaders, they often dismiss them as ”fringe economists,” or even more derogatively, as the Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang put it, as mere ”sociologists.” In short, we barely have any robust intellectual debate on economic policy in this country, even if clearly there is, as economist Jesus Felipe recently put it in a Manila House panel discussion, “something seriously wrong [with our state of economic policy-making].”

The same poverty of discourse extends to other relevant disciplines, including political science, which has, as correctly pointed out by historian Lisandro Claudio, broadly echoed ”good governance” talking points in recent years rather than properly theorizing the exceptional absence of a developmental state. Practically all of our neighbors have a decently robust bureaucracy capable of implementing a semblance of industrial policy. Why is the Philippine state so exceptionally “weak”?

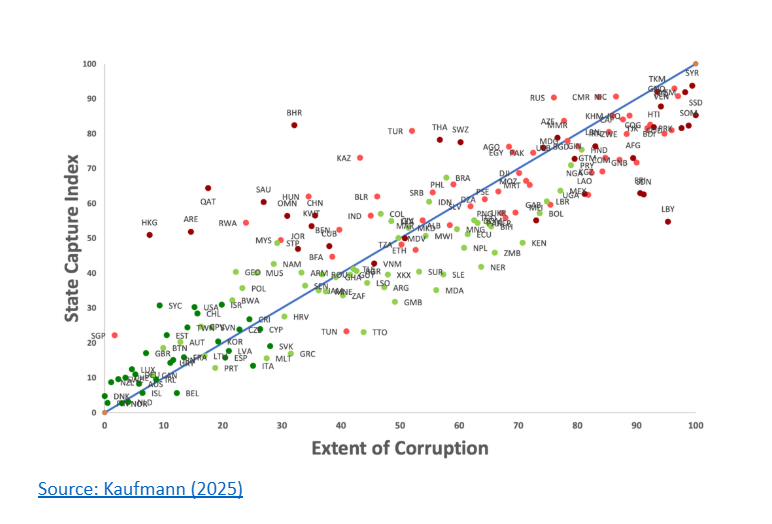

What makes this policy-relevant theoretical question even more puzzling is that the Philippines is a very ”average” state by global standards when one looks at robust indices. In an authoritative Brookings Institution study, one can clearly see that in terms of both corruption (i.e., usurpation of public finances), as well as even more pernicious ”state capture” (i.e., laws and rules crafted to the benefit of insiders) indices, the Philippines ranks better than far more developed countries, such as Turkey, Thailand, and even Brazil (and definitely Russia). Fact: We have a very ”averagely” bad/good state. Is it, then, the oligarchy? Interestingly, industrialized countries, such as South Korea, rank just as badly as us in The Economist’s ”crony capitalism index,” which measures concentration of economic productivity among a few major conglomerates.

Of course, oligarchy is just as bad as corruption. One of the most dangerous unintended consequences of catastrophizing the Philippine political economy in the absence of proper policy discussion, however, is reinforcing the populist strongman narrative. Having remembered everything but learned nothing from our disastrous experiences under former Presidents Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and Rodrigo Duterte, even the bulk of the middle class and highly educated voters seem to be gravitating toward yet another authoritarian iteration.

All authoritative surveys show that Vice President Sara Duterte is (still) a comfortable front-runner in the 2028 presidential election. Our pundits, however, keep on citing examples from the pre-Duterte era to argue that early front-runners are always disadvantaged. Never mind that the past decade has seen a tectonic realignment in our electoral landscape: the so-called “Solid South” ensures that any pro-Duterte candidate can rely on, at least, a fifth of total voters in any national election.

They only need ”kurot-kurot” votes from other regions to win back Malacañang. Thus, unless ”middle forces” coalesce around a singular, competitive, and compelling tandem, and forward a new policy agenda that ensures both honest (tapat) and competent (husay) governance, we are sleepwalking toward yet another ”strong leader” promising to magically solve our corruption and economic troubles with sheer ”political will.”

—————-

richard.heydarian@inquirer.net

Why I take the ICC probe personally