Sri Lanka beyond Ceylon

Colombo, Sri Lanka—This island country is still known by its former name Ceylon and all that it evokes: tea highlands, cinnamon coasts, elephants, monkeys, leopards, peacocks; an outpost of a British Empire on which the sun never sets. Indeed, half a century since this nation of 20 million people became a republic, changing its name from “Dominion of Ceylon” to “Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka,” traces of its colonial past are still very much present.

Perhaps there is no better place to glimpse its colonial legacies than the hill station of Nuwara Eliya, in the central highlands, over 1,800 meters above sea level. Just as Baguio City was for the Americans, Nuwara Eliya was developed by the British during Queen Victoria’s reign after their own image: one that is still reflected today not just with the colonial architecture but by the horse racetracks, Camp John Hay-like golf courses, and Burnham-like parks, where cricket—also introduced by the British—is played by local youth (the country’s victory in the 1996 World Cup remains a source of nostalgia and pride).

Galle Fort—cannons, ramparts, and all—meanwhile stands as a reminder that the Portuguese and the Dutch, too, colonized the coastal parts of the island.

Beyond these historic sites that are now major cities and tourist attractions, the island’s economy, society, and politics all bear imprints of its colonial past. Tea and rubber were introduced to the country by the British from the 1860s-1870s, shaping not just Sri Lanka’s economy but its very landscape—with over 200,000 and 100,000 hectares of its land devoted to tea and rubber cultivation today, respectively. Cinnamon—the “true” one, being indigenous to the island, as locals might add—was also the subject of much mercantilist desire and exploitation. The British strategy of “divide and conquer” planted the seeds of tension between the Sinhalese Buddhist majority and Tamil (mostly Hindu) minority, culminating in the bloody Sri Lankan Civil War.

Such colonial legacies and scars notwithstanding, Sri Lanka has ample grounds for asserting its distinct identity beyond its colonial past, as I saw in a brief sojourn around the island a third the size of Mindanao by car, “tuk-tuk,” and train. Hiking up the 2,243 m Adam’s Peak, the sacred mountain where the Buddha was supposed to have left a footprint, I am reminded of the country’s ancient civilization, with kingdoms like Anuradhapura (437 BCE –1017 CE) that predate even the Roman Empire. Indeed, one cannot be impressed—as Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo were—by this island, while visiting the Sigiriya Rock Fortress, Dambulla Cave Temple, or the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy, all World Heritage Sites.

What’s even more astounding about this country is not just its insular richness but its interconnectedness and cosmopolitan character. For Indians, the island holds a special place as the site of many events in the “Ramayana” (I saw a couple, including Ashok Vatika where Sita supposed to have been held captive), but it has long been a commercial hub long before the Portuguese ever set foot, making it unsurprising that Sindbad the Sailor himself is depicted to have sailed its seas. Far from being just an appendage of the Indian polity (it was never part of the British Raj), Sri Lanka also had strong cultural and economic ties with Southeast Asia, and historians speculate that traders from our own archipelago may have once traveled, even migrated, to their island.

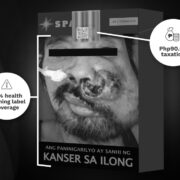

Today, amid a three-year-old economic crisis presaged by the 2019 Easter bombings, the island’s rich heritage is of little comfort to its people, and the 351 m “Lotus Tower” that rises above Colombo serves only to remind locals of their politicians’ pretensions—or unrealized aspirations. Amid severe inflation, routine power outages, and shortage of various goods, the university students I meet dream of better life abroad—in the Middle East and elsewhere. In 2022, mass protests led to Cabinet resignations and leadership change, but the political system has remained intact, dominated by dynastic, motorcade—traveling politicians. Inspired by former Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte, recent governments have used the specter of drugs as a populist trope, and a renewed anti-drug campaign called “Yukthiya” has seen 29,000 arrests since mid-December, prompting condemnations from the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and civil society groups.

Meanwhile, the roots of the 25-year Civil War, in which over 100,000 were killed, remain unaddressed; the Tamil-dominated north remains marginalized and militarized, with activists reporting harassment, surveillance and arbitrary detentions.

Despite these circumstances, tourists are coming back, offering a glimmer of economic hope, and the elections this year may yet break the political and economic inertia. Regardless of the outcome, there is so much going for this country—its natural resources, rich heritage, religious diversity, and friendly, generous people—and I believe that it can overcome its challenges and reclaim the prosperity it once held.

—————-glasco@inquirer.com.ph

Gideon Lasco, physician, medical anthropologist, and columnist, writes about health, medicine, culture, society, and in the Philippines.