Stunting: If feeding doesn’t work, what might?

Dr. Karol Yee, executive director of the Second Congressional Commission on Education (Edcom 2) recently wrote that our nutrition programs are “too little, too late.” I agree. Stunting isn’t solved by feeding, but by a package of nutrition and health interventions in the first 1,000 days, from conception to a child’s second birthday, when the diet and health of mothers and children matter most.

Yet as highlighted in a recent Senate hearing, very few government programs focus on this window. Feeding starts in day care and school, but by then the damage is often irreversible. So how do we “feed” pregnant women and young children, with dignity, at the right time? Lining up mothers for food may help in an emergency, but it doesn’t build a system that protects nutrition every month, for years. What might work better?

1. Put cash in mothers’ hands. The poorest households spend around 60 percent of their income on food, with the rest going mostly to health, clothing, and education. On average, less than 2 percent goes to vices. The stereotype that “they’ll just waste it” is not what the data show.

What the data show is this: when food prices rise, Filipino households tend to downgrade. They drop nutrient-rich foods and stick to staples like rice. This is especially harmful to pregnant women and young children. A full stomach is not the same as a nourished brain. If we want less stunting, poor households should be able to afford nutritious food.

That’s why our coalition supported the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) in designing and implementing a first 1,000 days grant under the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps), launched in February. The grant is given per child or pregnant woman, at P350 per month. The Senate is fighting to increase this to P750.

2. Tie cash to monthly checkups and nutrition counseling. What makes the grant powerful is not just the extra cash, but also the fact that it nudges mothers to bring their children to health centers for monthly monitoring. Procrastination is universal, especially among families who carry the mental load of daily survival. Long-term investments in health, like bringing a child for regular checkups when they look healthy, are easy to postpone.

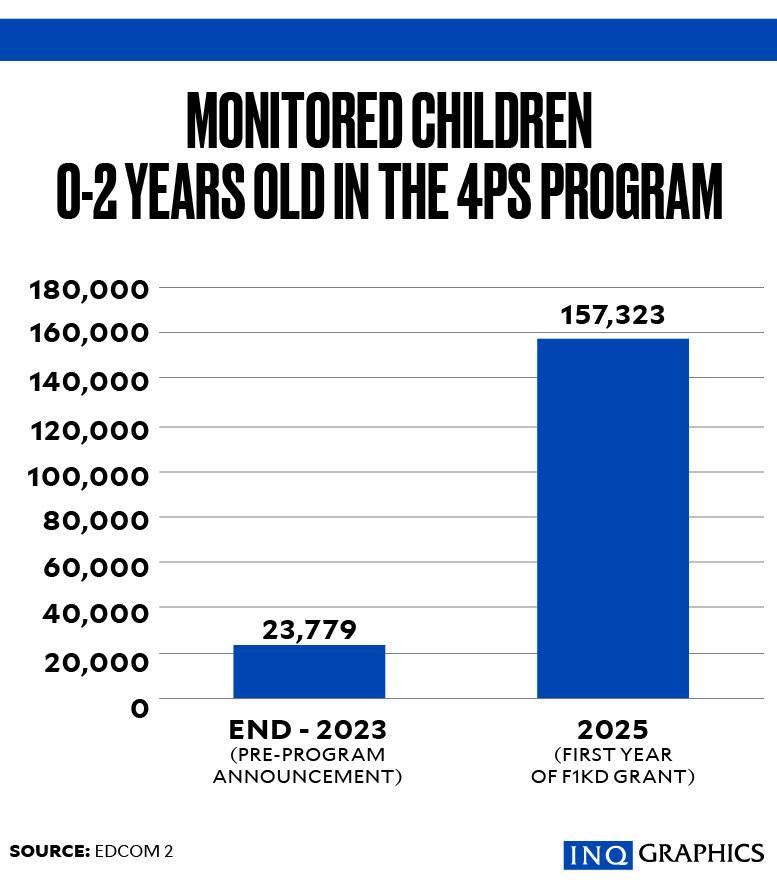

Before the grant, only 23,779 4Ps children under 2 years old were being regularly monitored by the health system. Since implementation of the grant, that number has jumped to 157,323. That’s a 6.6-fold increase. Cash, combined with conditions, brings pregnant women and toddlers into the health system earlier and more consistently. That is a big win.

The next challenge is this: is the health system good enough to meet their needs?

3. Use health financing to pay for child growth monitoring and malnutrition prevention. Here is where PhilHealth comes in. Local health units are overworked and underfunded. Growth monitoring, counseling, and follow-through for nutritionally at-risk children often depend on the heroism of a few midwives, nurses, and barangay health workers. Data show that local government units only monitor about one-fourth of stunted children.

If we want stunting prevention to be “every month, for every mother and child,” we need stable financing and clear incentives.

PhilHealth can pay for first 1,000 days services as a package, not just for curative care when a child is already sick. Following best practices, it can pay a fixed rate per child if a local health unit is able to bring that child into its “catchment.” Units that consistently monitor, provide health and nutrition counseling, and deliver supplementation can receive an additional performance-based payment. Once the monitoring and evaluation system is stronger, PhilHealth could even provide bonuses to local health units that effectively lower the stunting rate in their catchment. This structure is similar to the President’s Yaman ng Kalusugan Program primary care package.

Reformers in PhilHealth, DSWD, and other agencies are doing their best, but they cannot do it alone. They need our help in clamoring for stunting to be front and center in our development priorities.

—————-

Lyonel T. Tanganco convenes the Malusog at Matalinong Bata Coalition. He was a director at the Department of Finance and is taking up his master’s in data and economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. You may reach lyonel.t.tanganco@gmail.com for feedback.