The library’s place in a democracy

At a recent anti-corruption conference, I briefly chatted with a Bolivian man who is the convenor of a network of librarians and is an activist fighting corruption. My first instinct was to dismiss his involvement with libraries as an interesting hobby. But then it clicked: Public access to information is the bedrock of anti-corruption, so why wouldn’t the activist wear both hats?

I am not alone in forgetting the democratic underpinning of libraries. Due to their growing rarity, we tend to consider them ends unto themselves. They are sometimes treated like artifacts rather than civic spaces, the books inside reframed as relics from a literate past that must be preserved rather than as sources of information that should be consumed, considered, challenged.

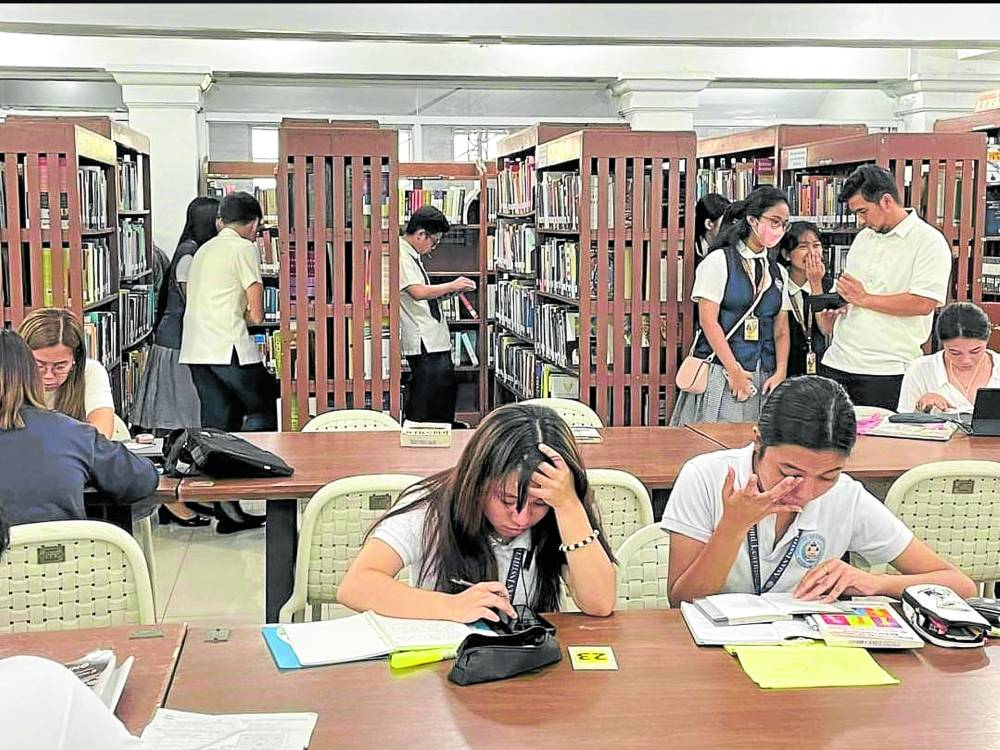

Often, our public discourse limits libraries to their educative role—quiet places, typically on campuses, where students can use reference books or work without interruption. This is a critical function, but it misses the forest for the trees.

In a democratic context, libraries are places where citizens can access information that helps them make informed decisions about who to vote for, which empowers them to hold those elected to account. This concept assumes that libraries are funded by the government in the spirit of making the democratic system work. At its best, the concept does work: In a world of misinformation and polarization, public libraries remain trusted places.

The world was reminded of such power in November 2023 when Russians shelled the Kherson Regional Scientific Library in Ukraine. The Russians continued attacking the library until it burned to the ground. The state-owned library boasted collections in 45 languages, most of them focused on the history and ethnography of southern Ukraine, including Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea. The library’s destruction was a political act, a strategic win in Russia’s occupation effort; if information about Ukraine’s history and society was unavailable, it was—literally and figuratively—up for grabs.

It is no wonder then that preserving and developing libraries is of low priority in the Pakistani state, which is more interested in suppressing inclusive politics and disempowering citizens. What hope can libraries have in a context where even social media musings are considered subversive and censored under any pretense? The information that public libraries offer, coupled with their ability to convene communities in real life, is a democratic force not to be taken lightly.

And so we have instead the proliferation of private libraries—in the homes of the educated elite, in private clubs, private schools and universities, and those under the control of vested community groups. Despite their private nature, this latter category continues to play a key democratic role, engaging local communities, providing access to otherwise obscure information, sparking debate through events, and, increasingly, providing digital access to world reference materials.

But these spaces are dwindling and increasingly threatened. This was evident in Dawn’s coverage of the Sayad Hashmi Reference Library, which is threatened by demolition as it stands on the proposed route of the Malir Expressway. Created and maintained through communal efforts, the library houses 16,000 books with a focus on Baloch literature and culture. Even as demolition day creeps closer, the authorities have yet to offer an alternative location for it. In a clear illustration of the political nature of libraries, its sponsors and supporters believe that this is due to its links to the Baloch community, with the library’s demolition perceived as part of a broader effort to suppress that community’s voice and access to information.

The idea of the library as a political battleground is not new in Pakistan. Some may recall the Western press’s gushing coverage of a small library that popped up in Darra Adam Khel at the height of the TTP insurgency. (TTP or the Tehrik-e Taliban Pakistan is an alliance of militant networks formed in 2007 to unify opposition to the Pakistani military). Instead of joining his father’s gun shop, a local graduate set up a small community library next door in the hope that reading would provide both understanding of and sanctuary from the region’s collective trauma.

Such examples should not be a one-off. Given the mounting democratic challenges in our country, it is time for civil society to reprioritize the role of the library. And this may best be done by going back to basics and celebrating the joy of reading.

Reading, after all, engenders empathy, the starting point for all engagement, understanding, and notions of fairness. Those qualities are the real fuel of functioning democracies. Dawn/Asia News Network