Who will defend the Constitution?

As the Philippine Senate flirts with the idea of dismissing the impeachment complaint against Vice President Sara Duterte without a formal trial, it is time to step back from the heat of the moment and ask a deeper question: What will this misstep cost us in the long run?

Impeachment is not simply a political proceeding. It is one of the Constitution’s most powerful mechanisms for maintaining the delicate balance between the branches of government and ensuring that no official—no matter how popular or well-connected—can evade scrutiny. The Senate is not being asked to convict. It is simply being asked to do its constitutional duty: to try the case and let the evidence speak. If the Senate refuses to hold a trial, the consequence will not merely be the protection of a sitting Vice President; it will be another crack in the foundation of our democracy, another precedent that allows convenience and calculation to outrank constitutional responsibility.

This is not the first time that the Philippines has navigated treacherous constitutional waters. The 1987 Constitution, now 38 years old, was born from the wreckage of a dictatorship. It has endured coups, people power revolts, and shifting political tides, but it has never been substantively revised. It has suffered, instead, from slow erosion—the incremental weakening of its principles not by frontal attack, but by avoidance, defiance, and tactical evasion.

We are reaching a critical point. If institutions continually fail to exercise their constitutional obligations, they teach the public that the Constitution can be bent, bypassed, or ignored. Worse, they make it harder to claim the Constitution as a credible shield when the time comes that the people truly need it. Over time, a constitution that is not defended in practice becomes nothing more than a relic—a document to be quoted in classrooms, but irrelevant in the halls of power.

Other countries have walked this dangerous path. In the United States, President Donald Trump’s impeachment trials in 2019 and 2021 exposed a similar fissure: when party loyalty overtakes constitutional duty, the system’s internal guardrails falter. Many American senators admitted Trump’s misconduct but refused to convict, calculating their political futures instead of weighing the constitutional stakes. The result? An emboldened executive, a damaged impeachment process, and a public left more cynical about the very mechanisms meant to hold power in check.

Here at home, the impeachment of former chief justice Renato Corona in 2012 demonstrated that the process can be wielded, but it also revealed its fragility. Questions of political maneuvering, selective accountability, and long-term impact on judicial independence surfaced. Now, as the Senate considers side-stepping the trial altogether, the danger is not just the evasion—it is the normalization of institutional retreat from constitutional duty.

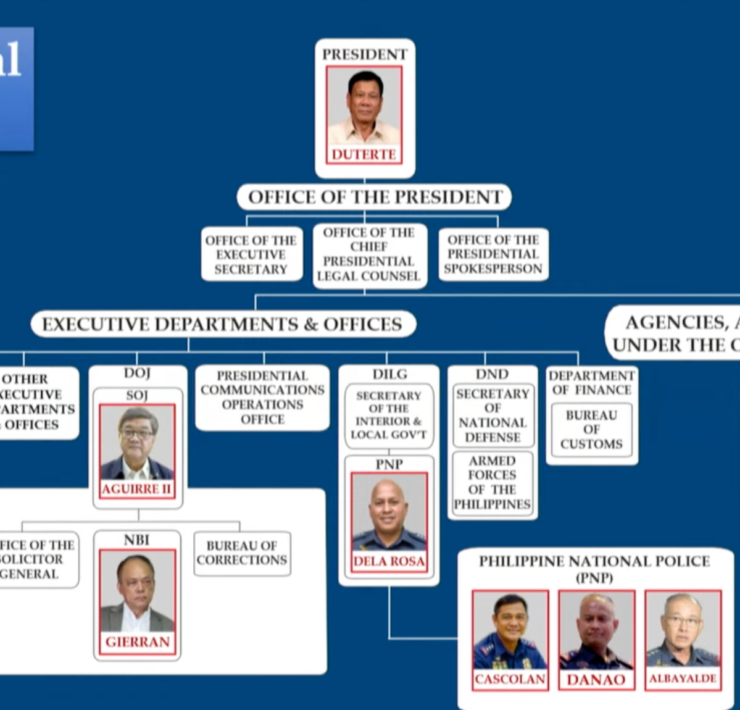

Who is minding the long-term consequences? Certainly not the politicians, who view impeachment only through the lens of the next election, the next alliance, or the next power play. Constitutional integrity has never been a strong vote-getter. But without it, all other reforms will rest on sand. We may be hurtling toward the same horrendous, wobbly constitutional regime Americans find themselves under Trump 2.0.

Where, then, is the source of constitutional defense? The answer is not only in the courts or the legislature. It must also come from the civic imagination of the people. In South Africa, during the constitutional drafting process in the 1990s, public education caravans were sent to towns and villages, asking ordinary citizens to weigh in on the clauses that would define their future. In Colombia, the 1991 constitutional reforms were propelled by student movements and civic coalitions that broke through the impasse of elite-dominated politics.

Perhaps it is time for the Philippines to revisit the Constitution, not through the narrow gates of power brokers, but through a wider conversation with the people. Constitutional vigilance must be decentralized. Citizens must become co-guardians of the Constitution, especially when politicians find it expedient to walk away.

The impeachment of Vice President Sara Duterte may seem like a tactical battle today. But if the Senate refuses to try the case, it may well mark a strategic loss for the Republic—not necessarily because of who wins or loses, but because we will have allowed one more brick to be quietly removed from the structure that holds our democracy together.

Edsa at 40: Remembering the lines we drew