Flooding and urban space negotiation

Cities maximize all the factors of the risk equation.

The “exposure factor” is inherently high due to population and building density that comes with convergence. The high “sensitivity factor” is due to the age of structures, with cities being the historic centers. The “vulnerability factor” is elevated by the presence of informal settlements and less serviced communities with below poverty threshold profiles. The “hazard factor” is due to the cities’ coastal or valley settings.

When dealing with flooding issues, these are the same factors that may be manipulated toward the desired risk level. Urban management can tap the bright side of cities, that are not only centers of innovation and technology but also hubs where human resources gravitate.

Hard infrastructure as default solutions

Coping with risk situations through infrastructure provision is often seen as the primary solution.

Governments invest in constructing sea walls, drainage systems, and other flood control structures. Some of the low lying cities are able to function through elaborate infrastructure forms of intervention.

However, not all cities have the financial resources to build infrastructure in the level of the MOSE flood control project of Venice in Italy or the dike systems of Amsterdam in the Netherlands. Low cost, and at the same time, long term alternatives need to be resorted to if cities are to continue delivering on their intended outcomes.

Land use, zoning, and the non-negotiables

Land is the most competed over resource in densely built-up cities. Land access negotiation is, therefore, intense and requires capacitation in terms of information and legal mechanisms.

Land use planning and zoning are urban management tasks that rest in the hands of local governments, which should be leveling the playing field. While “public interest” is difficult to define, planning as a political process should be able to target life protection and health safety preservation as the ultimate goal.

Enforcing laws covering protected areas, open spaces, air and water resources, ancestral domains and indigenous peoples should manifest in land use allocation and zoning ordinances. Regulating the direction of concentration of people and activities is necessarily preceded by the deliberate designation of areas for catalyst land development projects that draw people and stimulate more developments.

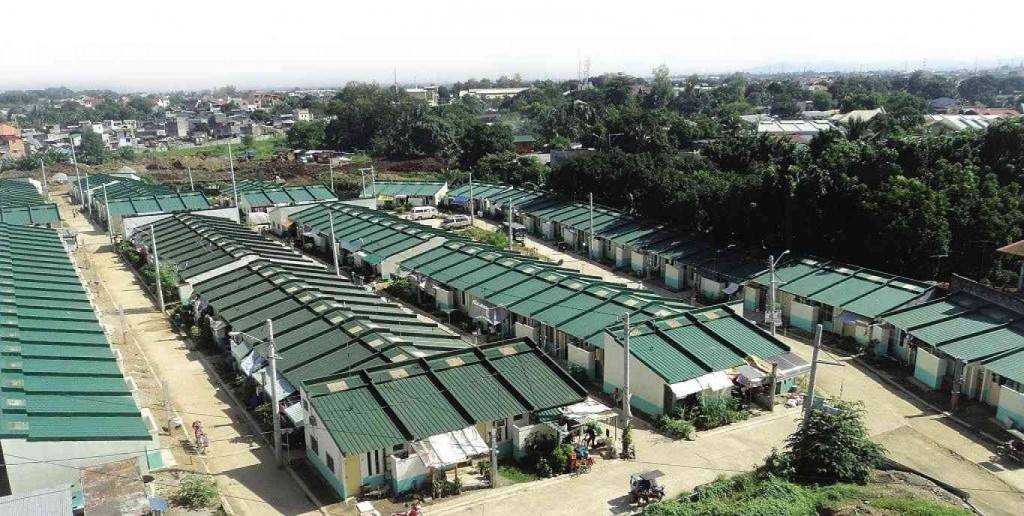

Public housing

In urban areas, those unable to assert their presence lose their foothold and are eventually driven out to city fringes or neighboring towns. Others who choose to remain are left to deal with the risks to their own safety while in many cases also posing risks to the rest of the urban citizenry.

Riverbanks, creeks and even the water bodies serve as sites for houses that people build themselves to remain as active participants in the city’s daily grind. Carrying out valuable roles in support of the manufacturing and services sectors based in the cities comes with efforts to address the work-home distance issue.

In-city housing underlies the cross-subsidy system of the Urban Development and Housing Act of 1992 which seeks to allot urban space for affordable housing as developers venture on open market housing. Freeing up easements and waterways have economic dimensions that call for viable alternatives to these makeshift housing in risk areas.

The vernacular and indigenous

Human interventions making up the built form of cities are sometimes referred to as the culprits in the aftermath of disasters.

But architecture is supposed to be about providing shelter, protection from the elements, enabling interactions. These associations are enhanced by designing with nature and designing in context. Architectural products can be radical additions to existing environments when designing is aimed at challenging and asserting power over nature.

As new building and development technologies emerge, designers of spaces need to refer to what has been effective in the past. Design principles embodied by vernacular architecture may be applied to modern structures.

The air ventilation and natural lighting allowed by the bahay na bato, the protection provided by the raised floor of the bahay kubo, the resilience afforded by the thick walls of Ivatan houses in Batanes are expressions of the intent to be one with the natural environment.

The negotiation process

Agreement and committing to common visions are the end products of the negotiation process.

Bringing in stakeholders to the negotiating table, with local governments facilitating the discussions among end-users, investors, technical experts, businesses and communities will better ensure the minimization of environmental risk factors.

Processing inputs and making definitive decisions involve weighing options vis-à-vis co-defined development paths.

Compromises and trade-offs are part and parcel of any negotiation process. With the ability to express and assert skewed in favor of the high-income group and those with positions of influence, it is the local government’s role to oversee the equitable distribution of limited resources.

Disruptions such as flooding come at great costs that are borne disproportionately by different social classes. Concerted efforts, driven by good governance, can mitigate the impacts of nature-induced environmental risks.

The author is a professor at the University of the Philippines College of Architecture, an architect, and urban planner