The city versus nature conundrum

What is urban? This was asked by my college professor during our team’s thesis consultation. The question caught our team off guard and I had to fumble an answer. Weakly, I responded with “urban is…not rural.” This anecdote has since become a recurring joke during reunions with friends over the years.

Even to this day, I would fumble for an answer to the question without resorting to definitions by negation. And even the most seasoned urban experts would be stymied to find a concise answer to something so pervasive as a city.

What is even more puzzling is why defining it by its opposite is so convenient. It highlights a striking dichotomy—that the city is the polar opposite of the country, just as the built environment is the antithesis of the natural, both being mutually exclusive domains, unable to coexist unless one is sacrificed.

Biology and cities

Society’s process of building has become linear and open-ended—unable to emulate the closed, circular flows of nutrients, carbon, information, and water that are the characteristic of thriving, natural ecosystems. Our cities do not behave like coral reefs or forests where nothing is wasted, resources are regenerated, diversity enables interdependence, and energy sources are inexhaustible.

And yet, biology has long been a metaphor for our cities. We speak of cities as organisms and of urban areas as ecosystems. The analogue is an important reminder of how we should view and design our cities, even if we fail to design them as such.

James Lovelock, the scientist and environmentalist who formed the Gaia hypothesis, even described how human presence is disabling the planet like a disease, and of which there are four possible outcomes: “destruction of the invading disease organisms; chronic infection; destruction of the host; or symbiosis—a lasting relationship of mutual benefit to the host and the invader.”

The latter is obviously the most desirable outcome, yet the most elusive.

No clear roadmap

Architects, planners, and ecologists have long aspired for this ideal, yet there is no clear roadmap to getting there. Even some of our approaches to addressing the culture-nature imbalance are flawed, aiming to be less bad than being more good.

For instance, we see carbon offsetting as a strategy to correct climate change, when a strategy of decarbonization would be more effective since it requires the radical shift from fossil fuels.

The term is ill-phrased, however, as it seems to imply that carbon is unnecessary, when in fact it is a crucial element for life. Carbon only becomes harmful when large quantities of it are left in the atmosphere or in our oceans rather than in the ground—a materials-in-the-wrong-place problem, as “Cradle to Cradle” authors Michael Braungart and William McDonough put it.

Alternative philosophy

Numerous environmentally-focused urbanists have offered an alternative philosophy—one where city and nature are intertwined, mutually beneficial, symbiotic, and synergistic, where each is made better by the other due to presence and proximity rather than by separation. These are the philosophical foundations that can turn the urban-rural situation into a nexus rather than a dichotomy.

Christopher Alexander proposed the idea that making architecture and human settlements is about making life.

Author and environmentalist Kirkpatrick Sale coined the term bioregionalism, or the ethic of living within the limitations of the environment. Society, he believed, must be a part of nature; that human ends and means must accommodate nature, not the reverse; and where people are liberated from distant and impersonal market forces, governments, and bureaucracies, instead finding a sense of oneness with the natural world.

Landscape architect Michael Hough looked at the city and saw that it was a human construction that could not be separated from the processes of nature. He described the necessary relationships that exist between human habitation and living systems and prescribed the development of urban environments that fit the processes of nature.

Getting there

Ken Yeang has long promoted the integration of nature into buildings. Singapore has adopted the idea of regeneration, particularly regarding water, more seriously than most countries. These are critical first steps in integrating society and ecology through the coupling of infrastructure with nature’s ecosystem services.

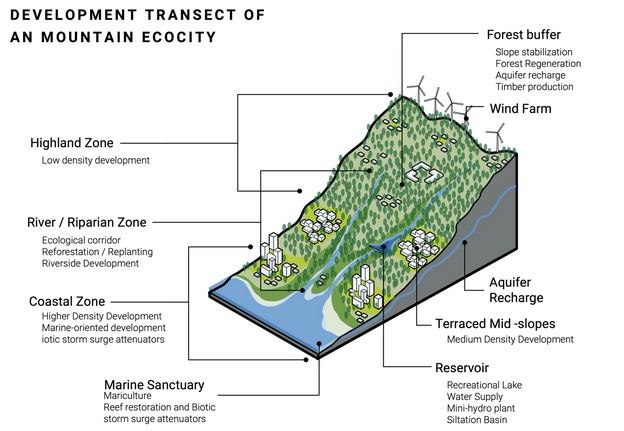

We aspire for livable cities but narrowly focus on human livability and ignore how we can create cities where all life thrives. What form of urbanism can be inserted into nature to form a mutually thriving ecosystem? Urban areas that are bonded to nature, where natural infrastructure blends functionally with built infrastructure.

Closed loop system

It is evident that the path we are on will not get us there. If we are to make this our ethos, the future has to be reinvented. Not only do we need to decarbonize our processes, but we will also have to mimic biological metabolisms in our buildings and cities—where the built environment harvests the energy of the sun, cleanses the air, recharges aquifers, and converts waste into nutrients to replenish the soil and nourish plants that will feed the city.

Envisioning such a closed loop system will entail redesigning everything. But what if we can? Or more importantly, what if we have to?

The threat of cities on nature is evident. Driven by economic forces, the natural environment is in retreat from urban development.

However, the damage will not be one-sided. The World Economic Forum says nearly half of the GDP of the world’s cities is threatened by nature and biodiversity loss. The survival of nature means the survival of cities.

Since the beginning of time, climate is the force that has shaped our natural and man-made worlds—our forests and coastlines, mountains and rivers, all of life and evolution. Even the rise and fall of civilizations are a result of our adaptation (or failure to do so) to the shifting forces of climate over eons.

Today’s shifting climate once again provides an opportunity for our society to adapt. Cities and nature are both essential to our survival. We can choose to stay on our present course, or choose to build an alternative where nature is the answer to the urban question.

The author is founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning and design consultancy practice

The author is a built environment professional and the founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning, architecture and property consultancy. www.jlpdstudio.com