The journey that built the Filipino home

We love our homes. It is where we rest, grow and nurture ourselves. It is where life is lived.

But how has the Filipino domestic space evolved through the years? And what shaped the Filipino home in the context of interior design?

PREHISTORIC HOMES

Caves provide the earliest evidence of how prehistoric Filipinos used interior spaces.

In the rock shelters of Angono, Rizal, primitive drawings were found on cave walls, representing the prehistoric man’s personal experiences and aspirations.

The cave dwellings showed his early sense of defining spaces spaces according to their needs. One particular furniture–the paga, a platform made of tree branches–served as a resting place located near the hearth or fireplace.

Lean-to structures, or roofs held by a stick, and tree houses eventually became answers to man’s desire for a home wherever their nomadic life took them, allowing continued connection to the exterior environment while providing a structure for rituals.

VERNACULAR STRUCTURES

When early Filipinos finally settled, they began building structures using materials available in their surroundings. Nipa walls with bamboo frames and slatted bamboo floors elevated from the ground became defining features of the balay.

The balay became the vessel of man’s life experiences and inside it was the bulwagan where many activities took place. It was an open space that served as the living, dining, sleeping, and prayer areas of the house.

A separate kitchen was connected to the balay, while the restroom was built far from it. Outside the bulwagan, people removed their footwear and washed their feet—a practice still common today. Within this space was the papag, where the farmer usually rested and neighbors often gathered to talk.

SPANISH INFLUENCES

During Spain’s colonial rule in the Philippines, houses were built around churches.

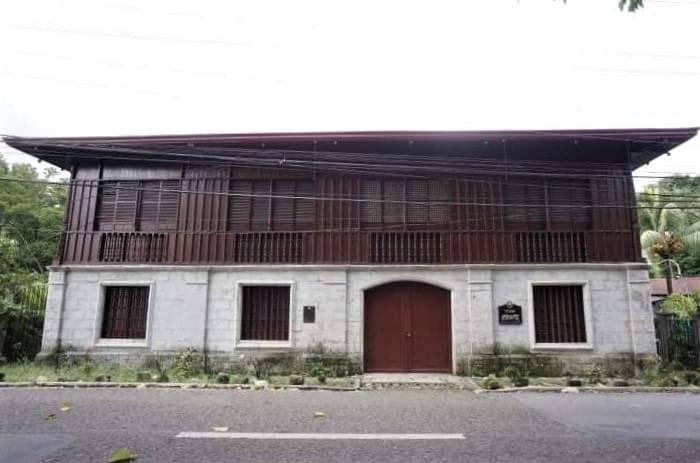

While houses in the early years remained similar to the balay in terms of materials and structure, the numerous earthquakes and fires that occurred led to the rise of the bahay na bato as the ideal house type of the era. Its larger size also became a symbol of Filipinos’ aspiration to be on the same level as their foreign colonizers.

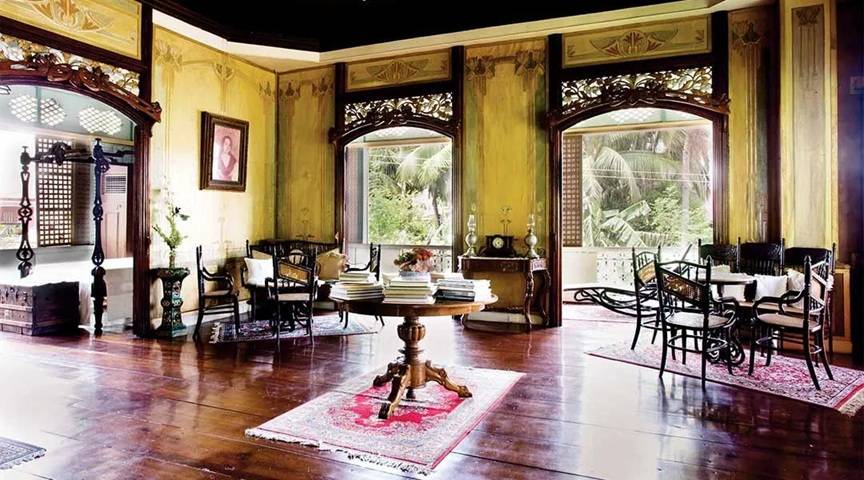

The bahay na bato had two levels, with the ground being the storage for carriages. On the second floor was the despacho where common folks were admitted. Friends and family were allowed to enter the caida and the sala which were the most decorated and furnished areas of the house. There was also an oratorio where the homeowners practiced their religiosity.

Interesting features of the house included the voladas, which were pathways for servants so they wouldn’t be seen walking through the main areas, and a peephole in the bedroom that allowed the master of the house to check whether or not he wanted to meet a visitor.

Several unique furniture pieces also existed in the bahay na bato, such as the silyang pamimintana, a high chair placed near the window for viewing processions on the street, and butaca, a lounge chair with long armrests used for resting or for childbirth.

There was also the gallinera, a bench with slatted storage underneath that served as a chicken coop for visiting common folk. Localized versions of foreign motifs were showcased by the Kama ni Ah-Tay, which featured the kalabasa motif.

Ventilation was addressed inside the bahay na bato through the punkah, a large fan hung above the dining table, and the callado which was a pierced latticework above the walls that embodied the sense of interconnectivity in Filipino spaces.

AMERICA’S BENEVOLENT ASSIMILATION

It was during the American period that hygiene became an important aspect of Filipino domestic life, as sanitary features and plumbing systems were finally incorporated into houses.

Homes used elaborate decorative elements that reflected Filipinos’ love for creativity and detail, as seen in the Floral Art Nouveau style popularized by artists like Isabelo Tampingco and Emilio Alvero, considered the first Filipino interior decorator.

With architecture and design used as part of the US policy of “benevolent assimilation”, the tsalet and the bungalow eventually became ideal house types because their raised floors resembled the form of the balay. Art Deco also emerged as a popular design style in the later years.

In terms of layout, the introduction of electricity made the silong livable through artificial lighting and ventilation, allowing living rooms, dining areas, and kitchens to be moved to the ground floor. The use of glass windows as a replacement for capiz also allowed rooms to bask in natural light.

POSTWAR NATION-BUILDING

After the war, the campaign for economic growth filled urban centers and led to the development of the walk-up apartment which became the home of low- to middle-income families.

The Dream House, developed by Ar. Cesar Concio, embodied the Filipino aspiration for quality family life. Though utilitarian and functional in nature, it became a haven that encouraged families to be active participants in nation-building.

The open and interconnected spaces of the past were replaced by rooms that provided privacy for family members, resulting in significantly less interaction. A “showcase attitude” also emerged as families displayed their affluence through their homes.

Wealthy Filipinos chose among popular design themes like Traditional, Contemporary, and Japanese styles, and began hiring interior decorators for professional work. Aguinaldo’s in Echague became a popular destination for homeowners who wanted their interiors professionally designed.

FROM THE 1960s TO THE 1990s

In 1964, the Philippine Institute of Interior Designers was founded to regulate the practice of interior design in the country, eventually leading to its licensure.

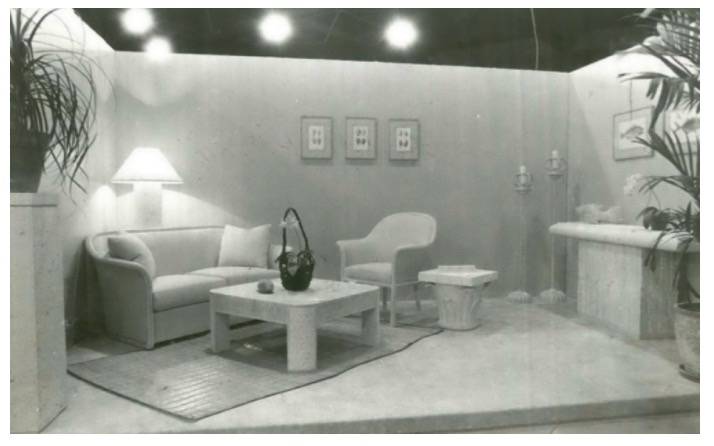

It became a sought-after career, with designers showcasing their expertise. One example was IDr. Edith Oliveros, who had a penchant for adding a Filipino touch to international styles and featuring classic eclecticism in her work.

The Mod style continued into the ’70s and produced an explosion of signs and symbols on interior walls. The “New Ilustrado Look” was introduced by Rosario Luz, who combined elements from the past with contemporary pieces to create elegant interiors. Built-in furniture and sunken living rooms also became popular.

The Neo-Vernacular emerged as a design philosophy in the 1980s, drawing inspiration from iconic folk forms and cultural patterns. The bahay kubo and bahay na bato continued to influence the Filipino house, as seen in the use of indigenous and local materials in the residence of National Artist for Architecture Francisco Mañosa.

“Recycled chic” became a trend in the ’90s as elements from old structures were used to style interiors amid the rise of sustainability and adaptive reuse. The integration of technology also paved the way for changes and adaptations in the Filipino home.

DESIGN IN THE NEW MILLENNIUM

Currently, more technologies are making an impact on interior spaces. With the rise of AI, smart technology is now being integrated into subdivisions and condominiums.

As for design styles, elements of Mexican and Balinese themes are now prevalent in interiors, reflecting both our Hispanic heritage and our close ties to nature, as noted by IDr. Nina Santamaria of Grupo Santamaria Interior Design.

THE CONCEPT OF THE FILIPINO HOME

The Filipino home has journeyed through a timeline that links the past to the present.

From historical design styles to current technological adaptations, the Filipino home continues to reflect our culture and value systems, which remain integral to the development and use of our interior spaces.

According to Dr. Raquel Florendo, our spaces reflect generations of traditions that continually shape our interiors.

Many influences may have originated from colonizers, but Filipinos embodied a sense of pag-angkin, or adaptation, that “Filipinized” what was foreign—such as incorporating the concept of the balay into the bahay na bato and the bungalow. These demonstrate how we, as Filipinos, preserve the things that matter most to us.

The Filipino space also remains grounded in practicality, aiming to produce designs that are comfortable and easy to use. The relationship between labas and loob continues to thrive as we develop new forms of interior design that embrace both nature and community.

For Dr. Florendo, the Filipino lens and pantayong pananaw offer better ways to see how our homes evolved. To her, the Filipino space is a collection of memories gathered through generations of traditions and reflected in our culture—something foreign observers will find hard to understand.

From the practice of oro plata mata, to the hanging of diplomas on walls, lucky charms alongside religious icons, and the keeping of heirloom pieces like furniture, décor or even structural elements, the Filipino space is a reflection of our past experiences and our present choices.

What, then, has shaped the spaces of Filipino homes? It has been formed by the fusion of what was available externally and by what was already within.

Source: Interior Design in the Philippines: A Retrospect of Spaces and Culture by IDr. Edith Oliveros and Dr. Rauel Florendo

The author has more than 20 years of expertise in designing interiors. Experience his designs by contacting him at (+63917) 886-0983