DINNER Q

Dinners were always important.

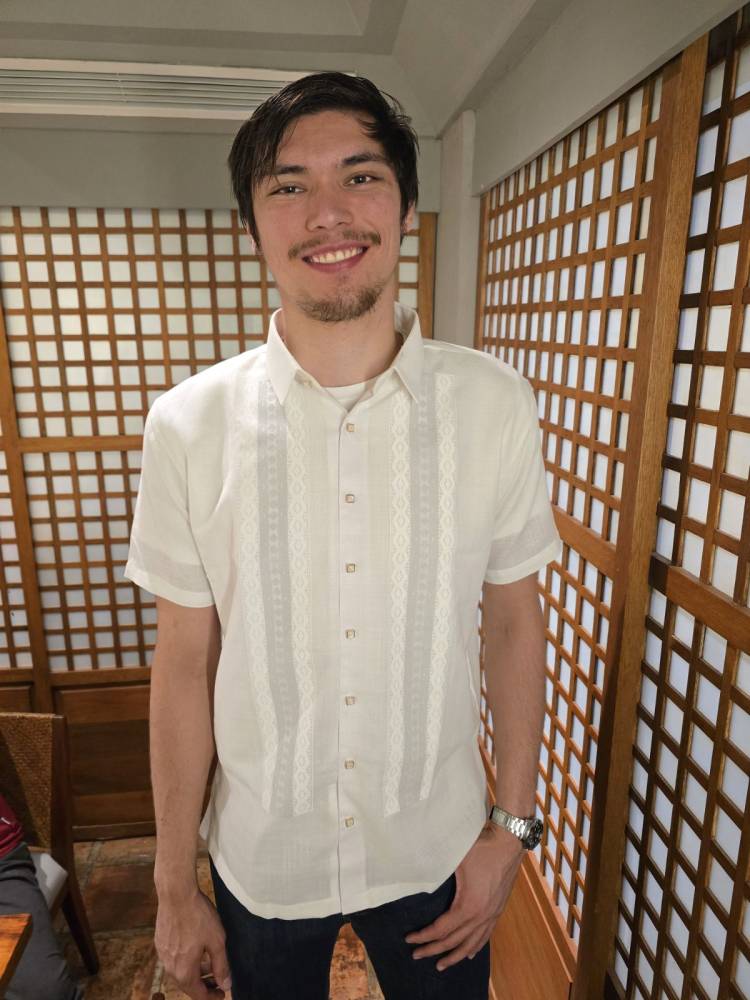

In 16 games with the University of the Philippines Fighting Maroons, Quentin Millora-Brown averaged 9.3 points, 9.9 rebounds, 1.4 blocks and 1 postgame dinner with family per outing.

From the opening tip of the UAAP Season 87 men’s basketball tournament down to the title-clinching Game 3 of the Finals against La Salle, Millora-Brown missed only one chance to have after-game supper with his relatives based here: It was the second meeting with the Green Archers in the elimination round when the high-IQ center had to fly back to the US because his grandfather died.

Except for that game, Millora-Brown saw action in all of UP’s matches—and then had dinner with relatives after each of them.

“After the game, he becomes the baby. My production assistant mode kicks in,” said Renacelle Cruz-Punzalan, an aunt on his mother’s side of the family who has worked with several local entertainment celebrities, including the actress Alice Dixson. “We wait for him at the arena exit, I get his stuff—bag, water bottle, whatever he’s carrying—so he can accommodate fans who want an autograph or take a photo with him.

“Then, we take him to where the dinner is, usually within the area where the game was held,” Cruz-Punzalan added.

The dinner fare was nothing more than the usual Filipino restaurant offerings. Lumpiang shanghai. Pancit bihon. One time, he was goaded into devouring balut and he gamely Fear Factor-ed his way through the popular duck egg delicacy.

The dinner itself, sitting down and chatting with relatives he hadn’t seen in a long time, mattered most.

“Having family dinners after the games and being able to connect with everybody is something that has always been an important part of my life,” Millora-Brown wrote in a message to the Inquirer. “My mom always prioritized sitting down to eat dinner together as a family, no matter what time or how busy our schedules were.”

“Having the opportunity to do that with family in the Philippines helped minimize feelings of homesickness,” the 25-year-old Maroons standout said. “When you have an immediate support group around you that loves you unconditionally, you can give everything you have and trust that even if you fail, family will help you back up and push you forward to the next challenge.”

Millora-Brown hit two crucial free throws that sealed UP’s 66-62 victory over La Salle in the deciding Game 3, providing a fitting cap to his one-year stint with the Maroons.

His stint with UP is often defined as one-and-done, a description that now seems trite—lazy, even—considering how deep his roots run in the school.

Starting with his late grandfather, Angel Millora, who finished his medicine degree in 1963, and grandmother Annette Lansang-Millora, who finished her pre-med course at the State University, Millora-Brown has had at least 12 relatives who studied in UP.

In fact, decades from now, when he has his own grandchildren to talk to the way his lolo Angel used to advice him about free throws when he was a kid, the story he said he would often tell about his one-season stay with the Maroons is not just the 16 games he played.

It would be about the decades that built his affinity for the school.

‘Memories of a lifetime’

“Most people don’t realize how deep my family connections to UP are,” he said. “I have many lolas, lolos, titas, titos, and cousins on both sides of my family who have graduated from UP. A good number continue to give back by teaching or working at UP. Our blood genuinely runs maroon.”

He may have been done in one season, but the journey that took him to his first game with UP was years in the making.

“From being able to don the Fighting Maroon’s uniform to winning the season 87 championship with my teammates, as well as deepening the relationships with both my Lola and Lolo’s sides of the family, I’ve had experiences and made memories of a lifetime,” Millora-Brown said.

And a lot of that journey was covered in those post-game dinners, where Millora-Brown formed several core memories with his relatives.

“The most memorable was the first dinner with Q (Millora-Brown’s nickname) after the win over Adamson in the first round,” said 49-year-old Chris Millora, an uncle. “It took us 45 minutes to get to the restaurant even though it was just a 10-minute walk from the [Mall of Asia] Arena. Quentin was very generous with fans wanting to get a picture with him. He really appreciates their support and gives back by obliging them.”

“We talk about anything—from Spotify playlists, reminders from his parents after every game, places he went to and ate at with his teammates,” said Cruz-Punzalan, 51. The two became material for podcasters who witnessed how Millora-Brown tried to fold his 6-foot-10 frame into her tiny Chevy Spark.

“We take turns bringing him home,” she said, “Depends on who brings a car to the game.”

Millora-Brown would often talk about his grandfather. He spoke about one of his favorite Filipino dishes—ampalaya (bitter gourd) with hot sauce. He would learn a Filipino word a day and flaunt those words during the dinners. He would laugh with aunts Bernice Mendoza and Ina Ocampo and marvel at even the littlest show of affection by his supporters, like when they gifted him with a water bottle, which his aunt, Peachy Cruz-Salvatera, personalized with a Chibi image of him.

“Family dinners are intimate occasions where he can let his guard down and simply be himself. He finds a rare space to express his thoughts and emotions openly, devoid of pretensions,” said his grandmother, Ellen Mendoza.

And sometimes, the need to express himself was urgent.

“Our dinner at Lola (a restaurant) … was a memorable moment because we were there for him as a family,” an aunt, 38-year-old Kamille Mendoza, said. “It was after a won game and we learned about the passing of Tito Angel, and we felt how he needed family at that time. There were no dry eyes at our table, we cried subtly. We were glad to be there for him.”

Millora-Brown took none of those moments for granted.

“Having the opportunity to connect with my family in Manila was huge to me,” he said.

There is a strong chance that he will pursue the next chapter of his career here—either as a professional in the PBA or a part of the national pool.

“I’m continuing to work with my agent on finding the perfect spot for me,” he said. “We know that the first year after college has a huge impact on the rest of my career, so we want to make sure that where I go next will check off many of our boxes.”

“Being able to play for my country would be a dream come true. I’m ready and hopeful for Gilas to call me up into the pool or roster.”

Whatever shape a career in the country will take, one thing’s for sure.

Post-game family dinners are non-negotiable.