Structure amid the wilderness: The broadsheet’s place today

Times have changed since the founders of Philippine Daily Inquirer launched this broadsheet. Journalists had emerged from a turbulent period. Surviving censorship, control and manipulation imposed by the martial law regime of Ferdinand E. Marcos, the press stirred to action after the assassination of opposition leader Benigno Aquino Jr. in 1983. It did what newspapers are designed to do, provide a public forum where citizens can converse, debate and argue, exploring the ideas of nation-building for a free society. This forum empowered Filipinos to resist, mustering the collective will to speak truth to power.

The fall of the dictatorship in 1986 enlivened the power of news. It was time for news organizations to regroup. Eugenia “Eggie” Apostol was among the first to test the media market in a new era.

The period of democratic recovery heightened the resolve of journalists to provide Filipinos with news that was verified and checked for falsehood, to chase after the scoop and be the first to publish. Filipino journalists were hailed for the efforts of a “mosquito press” which exposed the bankruptcy of the Marcos regime and its empty promise to build a “New Society.” It was an auspicious beginning for a newspaper to establish and record the intelligence of the day.

The leadership of Eggie Apostol signaled the publication’s readiness for the long haul, launching a paper that would project journalism as a tool for nation-building, holding the public captive with the power of information, forming the collective will to achieve the common good.

The times seemed ideal for different kinds of journalism. Filipinos were engaged in rebuilding and renewal, buckling down to lay the foundations of democratic practice, preparing citizens for free and fair elections, drafting a new constitution, engaging in politics that presented fresh faces and fresh blood so the old politics could give way to the new.

The media landscape could not have been more promising for the growth of a national press. The Inquirer was among the first to set up shop even as the new government had yet to settle and exercise its full authority. It made good use of the time and grew an enterprise that would last to the present.

Indeed, the times called for new kinds of news organizations and new formats. The Inquirer’s success is due to the leadership’s familiarity with the tried and true. It set out to capture attention with headline news, leaving every other news enterprise to follow its trail.

Completely different setting

Eggie Apostol as publisher and Letty Jimenez Magsanoc as editor helmed the editorial team. Both had the feel for the public pulse, in touch with popular tastes and trends. Street-smart, they popularized news, even as the paper presented analysis and a cohort of leading columnists who set directions for media discourse.

Times have changed since that golden passage. Both Apostol and Jimenez have left the field. A new generation of journalists has created a newspaper in a completely different setting. Legacy formats are now confronted with existential challenges as social media seized the momentum with the speed and pace of 24/7 news.

Keeping the broadsheet alive seems quaint in these times; one cannot help but wonder whether either Eggie or Letty would have wanted to keep it going, given the revolutionary changes in communication and its impact on the way people receive and relate to the news.

The question remains: what is the place of journalism in the ever-expanding landscape of communication? Where is the hierarchy of priorities, the preselection of the significant developments of the day. What to do amid the mindless mix of news, information, trivia and entertainment? The broadsheet and its noble tradition respond to these questions with courage and confidence.

Those of us who believe in the indelibility of ink on paper welcome the resolve with which the broadsheet is published daily. But the challenges to the practice of journalism raise questions.

The new generation of readers is a stranger to the format; the sequence of pages may make no sense to the newbie navigating its separate if fewer sections. The current audience picks up news according to a playlist in their heads. What sense of the intelligence of the day is imprinted in their minds has yet to be studied or understood.

A common need

Perhaps, the print edition exists for precisely people like myself who want to test how the news that flows through the wilderness of podcasts and TikToks stand up to the structured order of the printed word, its carefully selected photographs and thoughtful illustrations, its careful crafting of an editorial position.

I sense that this order, the framework that holds all news together, responds to a common need for interpretation and meaning. We understand the differences that set people and their communities apart, but their shared values manifest themselves despite these differences. The food we eat, our social manners may differ from place to place, but we are all essentially the same tribe wherever we are in the world. And news helps us to recognize this common humanity, despite the differences in culture, custom and religious beliefs.

News must be daily. News must be read. It is a source of continuing education that prepares us to interpret the changes in which we live our lives, or to sustain the serenity of our outlook because our communities have lived and survived some of these changes before and we are somehow prepared to embrace the strangeness of their coming around again, this cycle of occurrence and happenstance.

News may not last as literature does. But in the future, those attempting to understand their present are bound to turn to these first drafts of history to gain some understanding of what it all means.

Exposure to news, especially good journalism, makes it possible for us to understand and accept the conduct of the outsider because it is all part of our shared humanity.

Imperfect as these stories may be, events hyped with misplaced or misleading prominence—the news of the day serves to fuel the best minds to think on the possibilities these stories suggest.

Indeed, the value of news is enhanced by the quality of society in which it operates. Unfortunately, the quality of news enterprise has a lot to do with the efforts to create or the utter failure to build the kind of learning society in which citizens engage in discussions and debates, so they can understand their differences as well as their agreements.

The broadsheet is filled with possibilities. Let us will it a long and useful life.

***

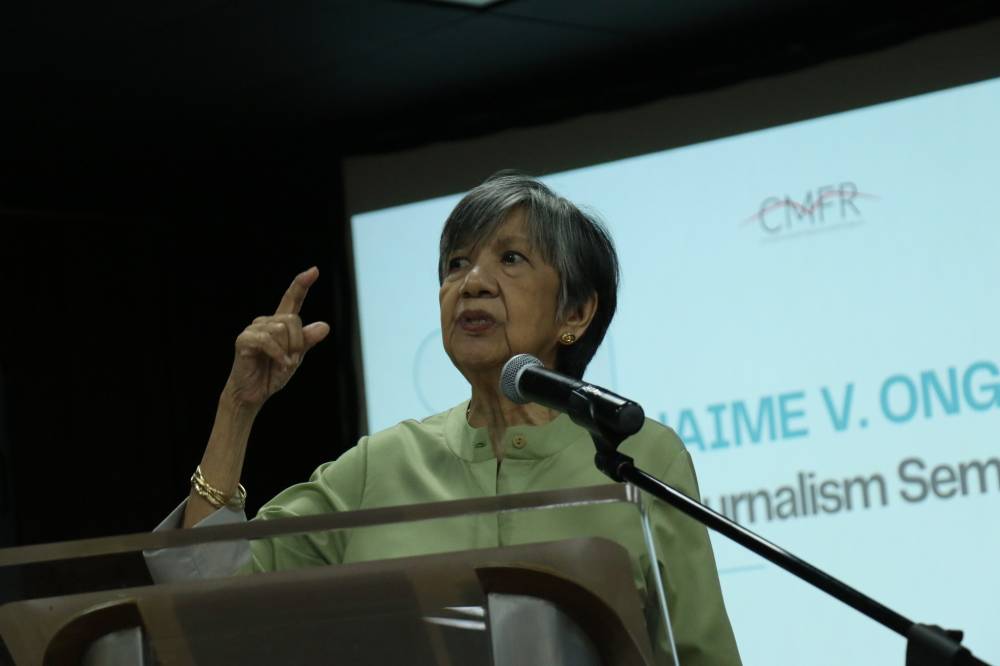

Melinda Quintos de Jesus is the founder and executive director of the Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility (CMFR), established in 1989. She conceptualized the institutional framework and design of CMFR’s core programs: media monitoring to promote professional values in the practice of the press, as well as press freedom protection. She also developed training programs on media and the justice system, human rights reporting, peace journalism, coverage of the marginalized sectors (women and children, LGBT, indigenous peoples), and other emerging issues in the news agenda. She wrote columns for Veritas NewsWeekly, the Philippine Daily Inquirer, and other major dailies.

She was a journalist-in-residence at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor (1985-86) and a fellow of the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy based at the John F. Kennedy School at Harvard University in 1995. A press freedom advocate, she was a founding member of the Board of Trustees of the Southeast Asian Press Alliance and the Philippine-based Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists Inc.; and the Freedom for Media, Freedom for All coalition.