Al Pacino and the disquiet of an actor who became a star

“I hope the perception is that I’m an actor, I never intended to be a movie star.”

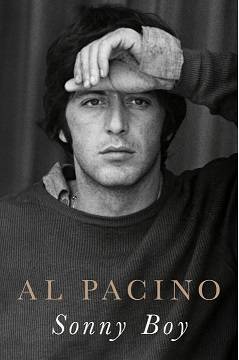

In his first memoir, Al Pacino does more than hope; he convinces us: His is a creative life lived in full. “Sonny Boy” (Penguin Press, 2024, 370 pages) gives a first-person account of how an Italian kid from a rough South Bronx neighborhood became one of the most accomplished actors of the last 50 years.

We know Pacino as a movie star simply because he is: You know his films even if you haven’t actually watched them. “The Godfather” series, “Serpico,” “Scarface,” “Scent of a Woman,” “Dick Tracy”—anecdotes from these iconic films are the milestones that guide readers of a certain age. Because they know how old they were when each of those iconic films came out, there’s no better device to convey the passage of time.

Why is Pacino adamant to be known above all as an actor? Because theater is his first and greatest love. After quitting Manhattan’s High School of Performing Arts at 16, he would walk around New York rehearsing Shakespeare. “In these side streets and passageways, I didn’t need anyone’s permission if I wanted to play Prospero, Falstaff, Shylock or Macbeth.”

In the 1990s, he wrote, directed, and produced “Looking for Richard”—a film that explores Shakespeare’s lasting impact on pop culture, particularly the highly regarded “Richard III.” His passion project, at 85, is a film adaptation of “King Lear.” His love for theater is akin to religion: He envisions heaven as that great Broadway play up in the sky.

“What do you think God will say at the pearly gates?” an interviewer asked. His reply: “I hope He says rehearsal starts tomorrow at 3 p.m.”

Gravelly voice

“Sonny Boy” is undeniably Pacino talking to you. You can almost hear his gravelly voice as you read. He shares candid photos from his childhood, theater days, and film career—all personally captioned—to paint a portrait of an actor who seems genuinely surprised by his own success. He shares, with great affection, anecdotes of stars he worked with: Dustin Hoffman, Robert de Niro, Emilio Estevez, Diane Keaton, and every famous director who was active from the ‘70s to today.

The most indelible stories, though, are not the ones about Hollywood legends but of Pacino’s beloved childhood friends. Cliffy, Bruce, and Petey called him Sonny, his mother’s pet name for him. They embody what Pacino’s life was and could have been, had he not made different choices.

“Around 1948, that’s when the drugs came into New York. That’s when the trouble started. Of all my dearest, closest friends from that time, none of them survived.” There but for the grace of God go I.

Grace was in the form of Pacino’s mother, Rose, who raised him as a single mother with the help of her own parents, who made sure Sonny Boy came home for dinner and stayed out of trouble. Pacino’s memoir is, ultimately, a tribute to his mother and everyone who kept him going: It’s the palpable gratitude and wonder at beating the odds that make “Sonny Boy” a rewarding read. We’re reminded that it takes more than talent to succeed, and that our personal lives are often more memorable than the stories we create.

“Sonny Boy” is available in Fully Booked.