Parliamentary, not federal: A Constitutional reform the Philippines can actually make work

Calls for Constitutional reform are growing louder, and it is easy to see why. Many Filipinos experience government as slow to decide, weak in execution and quick to dodge responsibility when things go wrong.

But changing the Constitution is not a symbolic gesture or a political reset button. It is a national gamble. If we choose to reopen the Charter, we must be clear about the problem we are trying to fix—and disciplined about the solutions we pursue.

The Philippines today faces two urgent imperatives. First, we need a political system that can govern competently—one that aligns power with responsibility and allows failure to be corrected without prolonged crisis. Second, we must protect national unity at a time of real strain—externally in the West Philippine Sea, and internally from inequality, disasters and the corrosive effects of patronage politics.

For these reasons, the more credible reform path is a parliamentary system within a unitary state—not a shift to federalism. But this argument comes with a critical condition: parliamentary government will not work without strong, disciplined political parties.

If party reform is treated as optional, parliamentary system will fail as surely as any other imported fix.

Two reforms often bundled, but not inseparable

In Philippine debates, parliamentary reform is often bundled with federalism, as if the two must come together or not at all. This is a mistake.

Parliamentary system answers a core governance question: How leaders are chosen and how they are held accountable.

Federalism answers a different question: How power is divided across territory. These are distinct choices. The Philippines can benefit from the accountability advantages of a parliamentary system without assuming the risks of federalism.

Many of the promises made in favor of federalism—more responsive government, policies closer to local needs, greater local initiative—are already achievable within a unitary system.

The problem is not just Constitutional design. It is whether institutions actually work.

Devolution and autonomy have already changed the landscape

The Philippines today is not the Philippines of decades ago. Devolution has expanded the authority and resources of local governments. More importantly, the Republic has already shown that meaningful self-government can exist within a unitary constitutional order.

The creation of autonomous regions—most notably the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region—settles this point. Within one republic, we have built asymmetric arrangements that respect history, grant real self-rule and support peace without diluting sovereignty or weakening national authority.

This experience weakens the case for federalism. The choice is not between rigid centralism and a full federal overhaul. The Constitution already allows autonomy when justified. What is missing is discipline: Institutions capable of turning authority into results and autonomy into responsibility.

Federalism is a risky response to a real problem

Federalism starts from a fair observation: Development is uneven, and many provinces feel left behind. But federalism is not the only response to this reality—and it may be the most dangerous.

- First, federalism risks deepening local capture. Where political monopolies already dominate, devolving more power can entrench them further. Without strong procurement rules, credible auditing, effective prosecution and civic oversight, federalism risks ‘constitutionalizing’ local fiefdoms.

- Second, federalism can exacerbate regional inequality. The different regions of our country have uneven tax bases and uneven administrative capacity. Federal systems attempt to manage this through equalization transfers and national standards, but these mechanisms are difficult to design and enforce even in mature democracies.

- Third, federalism complicates national coordination. Infrastructure corridors across the country, energy security, disaster response and connectivity require coherent standards and a clear chain of command. Fragmented authority makes decisive action harder, not easier.

- Fourth, federalism strains national unity. The Philippines is not a “coming-together” federation of previously independent states. It is a single nation managing diversity within a shared constitutional home.

At a time of heightened external pressure, reforms that fragment authority or multiply veto points deserve serious caution. A unitary state is not just an administrative choice—it is a strategic asset.

Why parliamentary system deserves serious consideration—if we fix parties

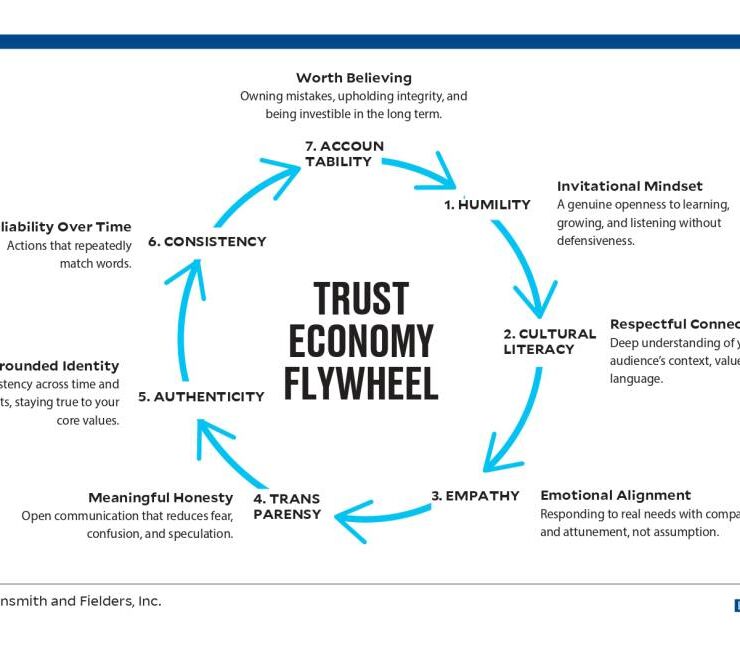

If federalism is a high-risk detour, a parliament framework addresses a core weakness of our current system: Blurred accountability and inconsistent execution. But the engine is not the prime minister. It is the party system.

Parliamentary government assumes parties that aggregate interests, can present governing programs, discipline members and be rewarded or punished by voters as a collective. This is where the Philippines has long struggled.

Our parties are weak and personality-driven. Coalitions form around candidates, not platforms. Turncoatism erases responsibility. Party switching turns elections into transactions.

Under these conditions, a parliamentary government risks either chronic instability or empty accountability.

That is why parliamentary reform must be paired with serious party reform, including:

• Antiturncoatism rules with real penalties.

• Clear, enforceable rules on party financing and transparency.

• Stronger internal party democracy, and candidate vetting and selection.

• Parliamentary safeguards, such as a constructive vote of no confidence, to ensure stability without impunity.

With these guardrails, parliamentary system offers real gains: Responsibility becomes visible; failed leadership can be replaced without national paralysis; and policy-making aligns more closely with execution.

Unitary for unity; autonomy for strength

Defending a unitary state does not mean reviving old-style centralism. It means preserving coherence: one republic, one citizenship and one national voice—especially when external challenges demand clarity and resolve.

Autonomy, properly designed, strengthens rather than weakens the nation. The Bangsamoro experience shows that accommodating diversity within a unitary state can reduce internal conflict, consolidate sovereignty and allow our country to face external threats with greater unity and strategic focus.

The task ahead is not to multiply political structures, but to make the ones we have work.

A reform worth making—or not at all

Constitutional reform should strengthen our ability to govern and our cohesion as a people. Federalism, in our circumstances, is a structural gamble that risks fragmentation, inequality and deeper local capture. Parliamentary system, by contrast, targets the dysfunction that defines much of our politics—if, and only if, we finally build political parties that matter.

If we are to amend the charter, we must do so with discipline: Adopt a parliamentary system to improve accountability, retain a unitary state to preserve unity, deepen devolution and autonomy where justified, and impose hard rules that force parties to become real institutions.

Anything less is not reform. It is risk without return.

The author is former president of the Management Association of the Philippines. He served as secretary of trade and industry, and president of University of the Philippines System. Feedback at map@map.org.ph.

Uncovering the Marcos siblings’ conflict: A case study