City of San Fernando on track to achieve zero waste

Many Filipinos know San Fernando, Pampanga province, as the Christmas capital of the Philippines—a title held dear by its over 300,000 residents.

But for environmental advocates, the urban center of Central Luzon has achieved a more enviable feat: It is arguably the only Philippine city on the verge of achieving zero waste.

Since the implementation of Republic Act No. 9003, or the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act, the city has put in place policies and infrastructure to help it comply with the landmark law.

By 2015, it had achieved a complete ban on plastic bags. By 2018, it was the only city that had achieved 80-percent waste diversion—meaning, only 20 percent of its waste went to landfills.

“In terms of looking at waste management, that’s a world-class number,” said Marian Ledesma, zero-waste campaigner at Greenpeace Philippines. “That’s a good example of how a city can implement all the right measures in place with the law.”

While national implementation of RA 9003 has been uneven, some local government units (LGUs) have emerged as models of effective waste management.

Ledesma and Jove Benosa, program manager for EcoWaste Coalition, both attribute San Fernando’s success to a combination of policies and community engagement. Among others, the city enforces a “no segregation, no collection” rule, mandates composting of organic waste, and has banned single-use plastic bags.

These were all done in partnership with Mother Earth Foundation, which played a crucial role in supporting San Fernando’s initiatives from the outset.

Evaluating RA 9003

Some 24 years after RA 9003 was implemented, only 22 local governments have made some progress in achieving zero waste, said Benosa. This includes San Fernando, the island municipality of Siquijor, and some barangays in Navotas and Malabon cities.

Their progress, he said, was propped up on “well-thought-of, well-crafted solid waste management systems” that targets waste at the source, not just at disposal. “Right now, much of (the country’s) approach toward solid waste is toward end-use. But what we are promoting is the idea that consumption itself must be sustainable, and not to have a throwaway or wasteful lifestyle.“

Added Ledesma: “It’s also more than a lifestyle or a choice that individuals make. It means changing our system… [shifting] away from linear and extractive economies and moving toward a system-wide reduction in resource extraction, reducing production and consumption.”

Coincidentally, January marks International Zero Waste Month, a monthlong initiative to raise awareness about waste reduction and encourage sustainable practices. It’s an especially timely reminder for the Philippines, which is currently grappling with a mounting garbage and plastic pollution crisis.

This despite the passage of RA 9003, hailed as a piece of progressive legislation that provided a legal framework for improving the country’s solid waste management system.

Its key provisions include requiring LGUs to divert at least 25 percent of their solid waste away from landfills, create a non-environmentally acceptable products (NEAP) list to phase out environmentally harmful products and packaging, close open dumpsites, and segregate solid waste at the source.

But “after two decades of implementation, the program may not be seen as progressively achieving its goals and objectives, as manifested by the steadily increasing volume of generated solid waste, including the many gaps noted in the program implementation,” warned a 2023 Commission on Audit (COA) report.

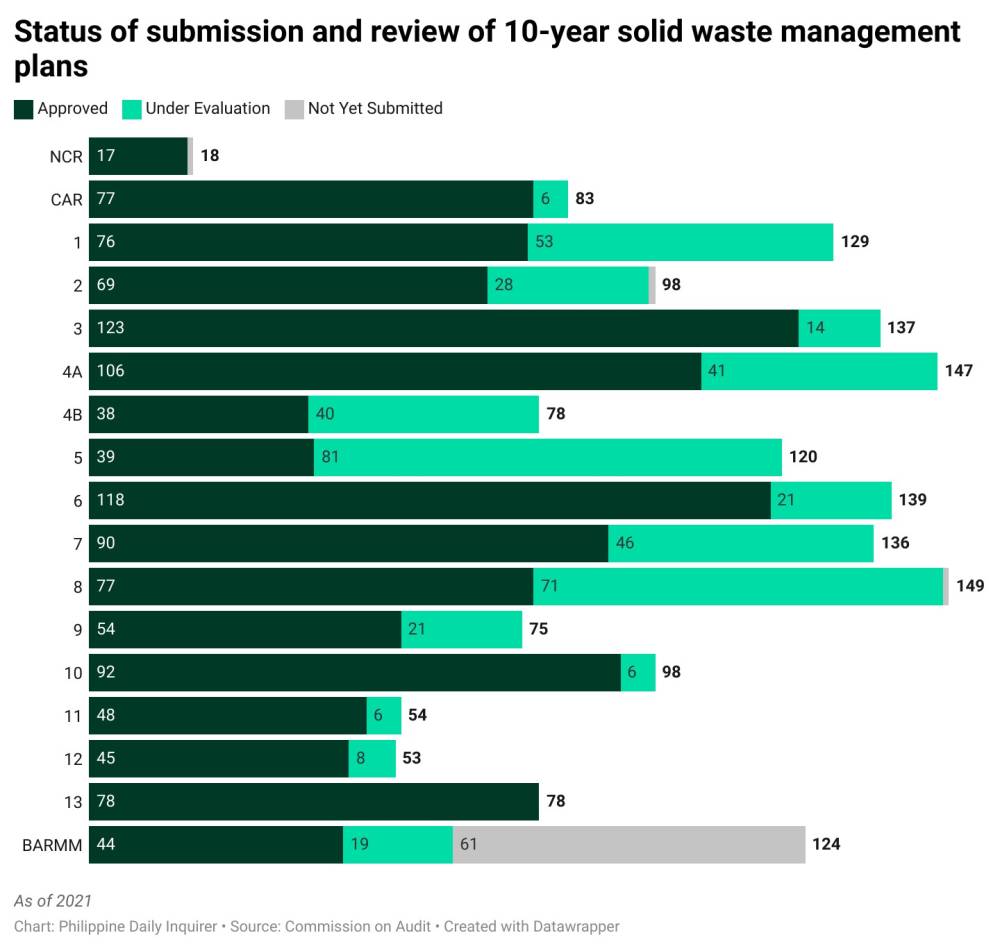

Since the law’s enactment, solid waste in the country has only nearly doubled from 9.07 metric tons in 2000 to 16.63 metric tons in 2020, the COA said. At the same time, many LGUs have yet to comply with forming local solid waste management boards, submitting solid waste management plans, and establishing materials recovery facilities.

A key failure is the long-overdue release of NEAP, which was supposed to be released a year after RA 9003 was enacted, Ledesma said. It was only last year that the Court of Appeals finally issued a writ of kalikasan requiring the state to, among others, release the list —and the government in turn has promised to do so within the next six months.

“Hopefully,” Ledesma said, “that list will also include single-use plastic products that are contributing to the plastic crisis the Philippines is currently facing.”

Drawbacks

At the same time, the Philippines’ solid waste management strategies continue to rely heavily on landfills despite their environmental and health drawbacks. Both Greenpeace and EcoWaste advocates believe that landfills merely address the end of the waste cycle and cannot be a sustainable solution to waste management.

Not to mention the looming landfill shortage: Currently, there are 343 operational landfills servicing 748 out of the country’s over 1,600 local government units, according to the Environmental Management Bureau of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). These might soon be insufficient for the over 19,000 tons of waste that come in every day.

Another contentious issue is the rise of waste-to-energy (WTE) projects, which some officials view as a solution to the waste crisis. However, Greenpeace strongly opposes this approach, citing its environmental and economic risks.

“Many say this would supposedly solve the waste management problems, but it overlooks the fact that waste to energy as a practice also has a lot of negative impacts on communities, on the cities themselves, and it also adds to greenhouse gas emissions,” she said. “If you’re talking about burning residual waste like plastics, those are essentially fossil fuels in a different kind of form. And you’re replacing solid waste and plastic pollution and changing its form into air pollution as you’re burning all of this waste.”

At the same time, she said, WTE facilities essentially run counter to the idea of zero waste as they in fact incentivize cities to generate more waste to incinerate for energy. In the United States, some cities have abandoned WTE projects after facing significant financial and public health challenges.

What works for others

Benosa said LGUs are more likely to achieve zero waste if they demonstrate strong political will to maintain these programs even with changes in administration.

“In our audits we see that there are some LGUs that already have policies in place but these are hardly enforced, or they were not able to train people, so they ultimately struggle (to comply with RA 9003),” he said.

While solid waste management has been decentralized to the LGU level, the national government through the National Solid Waste Management Commission led by the DENR must still harmonize and make coherent these LGU plans.

“It won’t work for example if Quezon City has a single-use plastic ban but once you go outside Quezon City, you can use it,” Benosa pointed out.

It’s also important to keep educating the communities and help them change mindsets in a country where “sachet culture” has become ingrained, added Ledesma.

“Some Filipinos are quite apprehensive (with zero waste) because the only alternatives that they encounter are in fancier, zero-waste stores, so they don’t feel that it’s accessible to them,” she said. “It’s why we’re advocating to bring it to the barangay level, at the sari-sari store level, and to give an option to small businesses to go plastic-free.”

Both stressed that the waste crisis must not just be on the shoulders of individuals but on the businesses and corporations that shape the waste cycle.

“And when those alternative systems are now in place, that’s when individuals, consumers, and communities can come in to really maintain that, to keep it running, to participate in them,” said Ledesma.