Hybrid teaching

Just when I was getting used to taking the point-to-point (P2P) bus from Ayala One to UP Town Center, the system started to fail. Buses caught in traffic would be late or, worse, miss scheduled departure and arrival times. When a bus was decommissioned for repair, it starts a chain reaction affecting all the routes for the day. Such is life for commuters in Metro Manila these days. The upside is that authorities have finally seen the light and now allow P2P buses to use the dedicated Edsa Carousel bus lane that leaves everyone else in the dust.

All we need for this solution to fail is for pasaway riders who weave in and out of the bus lane and an impatient congressman who wanted to scrap the bus lane and put his chauffeur-driven convenience over everyone else taking public transportation. Small victories in the battle against traffic snuffed out by entitlement and individuals who refuse to yield to the greatest good for the greatest number.

Traffic being what it is, I long for online classes. Everyone knows a fully online class is not ideal for undergrads and K-12, but one would think that hybrid (half online and half face-to-face) is the way to go. If properly coordinated, teachers and students will only have to endure the commute to and from school half the time. With such a system, scarce classrooms can be evenly distributed. Traffic will be lessened, our carbon footprint, too.

When we heard about the dismal ratio of computers to teachers and students in the public schools during the Congressional budget deliberations, it is not enough to be upset. There should be a revolt, simply because so many of the much-needed computers lay wasted, undelivered in bodegas of the Department of Education (DepEd). If we return to the growing pains of online teaching during the pandemic, we realized that, in principle, the internet was supposed to level the field by providing almost universal access to information.

In reality, the problem was not just having the right gadget: desktop, laptop, tablet, or smartphone. The real hindrance was that not everyone had access to stable, high speed internet connection. Even if DepEd delivered the gadgets, without electricity, a good internet service provider, or load, getting online was not possible. During the pandemic, my university provided an internet subsidy to enable us to work from home. That subsidy and the flexibility to work from home is now a thing of the past.

In the time we were teaching online, I noted that 30-40 percent of my students were outside Metro Manila. Isn’t it possible to organize the non-Manila students into a block, allow them to maintain distance learning for half the semester and only ask them to come in for three or four weeks of intensive in-person course work? Parents and students can also save on renting a space to stay in Manila. Of course, not all classes can be done online or hybrid, but those that can should be allowed to do so and return time and lives wasted in traffic or commuting.

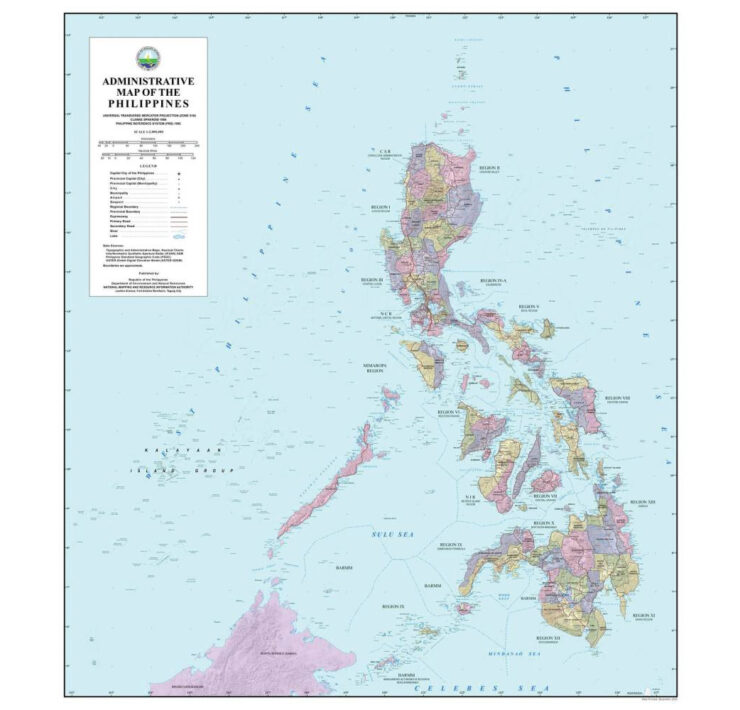

I’m currently teaching an online graduate course on public history in the University of the Philippines Baguio with half the students Baguio-based, some on the outskirts of Baguio like La Trinidad, others further afield: Pangasinan, Los Baños, and Mindanao.

My main challenge during the pandemic was not the Canvas learning management system, because long before the pandemic, I was already using a free LMS called Edmodo that had a friendly platform as easy to use as Facebook.

Edmodo revolutionized the way I teach, because all my required readings were in the system, students did not need to look for these in the library, nor spend time and money on bad photocopies. All course requirements were submitted online, thus saving trees and paper. It also set a strict deadline. If a paper was even one second late, the app would lock or accept with a time stamp that let the teacher know how late the submission was. Today, my LMS can check for plagiarism and I guess even artificial intelligence-generated submissions.

The way I had hoped things would turn out would be for most of the course material available online as: recorded lectures, readings, and assignments with face-to-face meetings, not for lectures but primarily for conversation, for reports, for a deepening of the course material covered online. Teaching online during the pandemic also made me rethink measures of learning. For example, I would give a low-stakes, online quizzes that gave the correct answers after the test. Then LMS gave the students the chance to retake the test and get a perfect score. Naturally, some people said this was improper and contributed to grade inflation. My argument is that a student who learned from their mistakes, has already learned something. They can show their mettle in major assessments like term papers and oral exams, not quizzes taken more for attendance than a grade.

Education is at a crossroads, and I hope we embrace the benefits of the pandemic and not throw the baby away with the bathwater.

—————-

aocampo@ateneo.edu

Ambeth is a Public Historian whose research covers 19th century Philippines: its art, culture, and the people who figure in the birth of the nation. Professor and former Chair, Department of History, Ateneo de Manila University, he writes a widely-read editorial page column for the Philippine Daily Inquirer, and has published over 30 books—the most recent being: Martial Law: Looking Back 15 (Anvil, 2021) and Yaman: History and Heritage in Philippine Money (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, 2021).